To get where you want to be, you have to do much more than you think it’s going to take. You must increase your actions by a factor of 10. — Grant Cardone, The 10x Rule

The Chirico Tenpeat has been on my radar for a couple of years, in the same way that a dear great Aunt’s birthday is on your radar. Which is to say that when Facebook reminds you on the day of, you curse out loud because it’s too late to send a card. In past years, this free “event,” held in the middle of the workweek, always seemed to defy my online searches until the day of, making it impossibly late to rearrange my work schedule to attend. This year, however, I happened across a post in February, announcing the 2019 Tenpeat on April 24, and I promptly took the day off. (I’ve since learned the event occurs on the last Wednesday of April every year, and hence perhaps not to difficult to plan for).

Climb #1 of 5. Taking it nice and easy.

The Tenpeat, about 30 minutes outside of Seattle, follows Tiger Mountain’s Chirico Trail to Poo Poo Point, 3.8 miles round trip with 1760ft of climbing. The aim of the Tenpeat is, you guessed it, to do this trek 10 consecutive times, for a total of 38 miles and a whopping 17,600 feet of ascend and descend in a single, 12 hour push.

Taking the whole effort quite seriously.

While an impressive number of people finish a full ten repeats annually (14 this year, including one who, no joke, paraglided down from the top on a couple of runs), race organizer, Jess Mullen, encourages people to come out for as many repeats as they can do, which for me, as a first-timer, was five, in a leisurely 8 hours and 14 minutes.

No more jacket and no more gloves. The day begins to warm up just after noon.

My “down” legs gave out before my “up” legs. Having completed the Yakima Skyline 25k with 5000ft of gain and 5000ft of descent just four days before, I was fatigued coming into the day. Moreover, I’d planned simply to use the experience for “time on feet,” deciding even before my arrival that I would complete as many repeats as I felt like, accounting for socializing time, without any real goal in mind.

Wobbly legs on the final descents. But I look so cools in my sunglasses, it’s hard to tell.

Still, my head is already spinning on 2020. For certain, I would need to treat this as a “real” event (with a hilly, 50 mile-esque training plan), and not the “fun run” I treated it as this year. And, given my best time on what I would consider to be an equivalent course is 12:59, a sub-12 Tenpeat feels like a good, solid stretch goal.

I’ve already blocked the day off on the calendar.

“I’ll get you some Greek salad,” I told Patrick, popping up from my camp chair and making my way to the long table, stacked with burgers, salads, chips and cookies, the thwap thwap of my flip flops signaling my steps away and then back again.

Over the course of the morning, Patrick and I had made our way separately to Randle High School, and the finish line of the Bigfoot 200, a 206.5 mile, point-to-point race in central Washington. While I was a bit lighter on my feet by virtue of the fact that I’d finished before Patrick and, hence, my legs were a little more rested, the real reason I offered to fetch him a snack was his feet: they were blistered to shreds.

In fact, nearly everyone’s feet were bandaged and sore. Individual toes; all the toes; heels; balls; pads… if you didn’t know better, you might think this groups had spent the morning standing atop hot coals, rather than making their way over 42,000ft of elevation gain and descent, taking 60-105 hours.

Everyone’s feet, but mine.

Sure, my pedicure had faded over 206 miles; and I had dirt under my big toenails, but there was little other evidence I’d been on my feet for 96 hours and 54 minutes straight; wading through stream crossings and crunching through gravel. Hearing other runners’ stories of footcare debacles in the past made me suspect I had “good feet,” but it wasn’t until Bigfoot that I realized my feet weren’t just good; they were blister-resistant, magic unicorn feet.

And my magic unicorn feet meant that what I had endured for much of my race (or, more accurately, what I had not endured) was very different — far easier — than what others had endured. I’m not the fastest; I’m not a naturally gifted runner; but my magic unicorn feet will always give me an advantage.

It’s easy to look at elite runners and think they have all the advantages, but the truth is, we all have advantages. Like the super-supportive spouse that makes lunch after a long run; the really good job that affords a private coach; lungs that are impervious to the effect of high altitude; or magic unicorn feet.

An epic 8.5 hour training effort in the ice, snow, slush and mud of a Pacific Northwest winter.

And I think about this, as I sit in a pedicure chair 20 hours after completing an 8 1/2 hour training run so muddy, slushy, and sloppy that I had to wash my worn socks twice to get the dirt out of them. But my unicorn feet are blister free.

Advantage: Me.

20 hours post-race: sandal ready!

It’s been nearly six months since my last blog post, the longest since I began writing about my running in 2016. That post, from July, was about a heartbreaking DNF, perhaps leading a reader to believe that my running life subsequently fell apart. That’s not what happened. Instead, I completed my first 200 mile race in August.

Mile 180 of the Bigfoot 200. 3:30am on August 14, 2018.

200 miles! You’re thinking. Why the hell didn’t you write about that!? I don’t have a great answer. I was tired, mentally and physically. I didn’t have adequate words. For the first seven months of 2018, I put everything I had into that race and, when it was over, I experienced the deep, post-race depression that many feel but it was a first time for me. I started hanging out again with the friends (and the husband) I’d abandoned all summer in the name of training. I ate and drank with abandon and put on 11 pounds. I started a new job and began traveling excessively. And I didn’t know how to get back… to whatever I was trying to get back to.

On December 2, I watched the live Twitter feed of the 2019 Western States lottery draw in California from my phone while sitting in a bistro in Paris. Western States is my dream. I don’t have a bucket list; I have Western States. But it is notoriously difficult to get into for non-elites like me. Some have waited up to eight years to hear their name called in the lottery; this was only my third year trying. Two hours and one bottle of wine later, I would need to plan for a fourth year.

So I looked to 2019. I contemplated the Moab 200, but I didn’t feel mentally ready for the build up to another 200 miler. I settled on the Burning River 100 and the Javelina Jundred, both Western States qualifiers, the latter having been on my “to do” list for a while. I’d committed to running R2R2R and the Born to Run 4-day, each somewhat of a lark in a way only ultra runners understand the definition. I registered for the CCC lottery, part of the UTMB series, because I had the qualification points to do so and decided it would probably be fun if I got in, but not because I really had a fire in my belly for it. And I restocked my refrigerator with kale and La Croix.

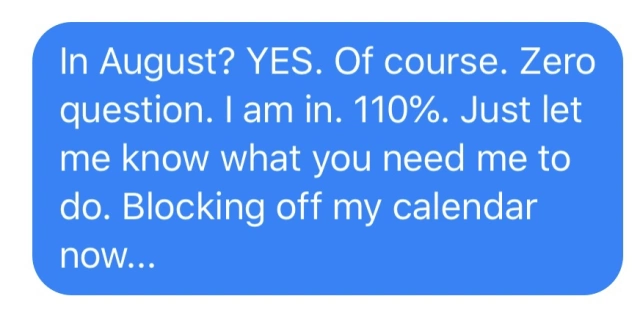

On January 3, the message came.

Would I pace Tracie’s friend Lisa, another member of our 10,000 person online running group, the final 50 miles at Leadville? Fly from Seattle to Colorado and run more than 12 hours through the night and above 9000ft with someone I’ve never actually met? Because Leadville is sitting in her heart and in her gut and she wants it so badly but it scares the shit out of her? (Because I know exactly what it feels like to teeter on the edge of crushing self doubt and something epic?)

I couldn’t respond fast enough.

And so this is what it feels like to be back. This is 2019…

Once my brain decided it was impossible, my heart stopped trying.

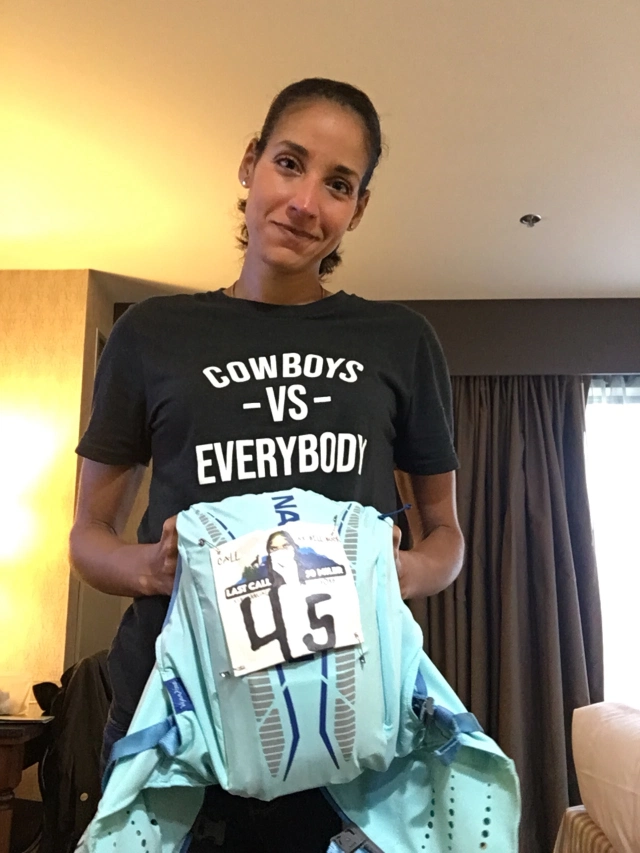

The Last Call 50 Miler was meant to be a perfect race. Scheduled for July 8, it was five weeks after an epically difficult training month in May, punctuated by a 50-mile race with more than 12,000 feet of climb, followed by a 13-hour race in which I broke the course record, followed by a 150-mile race, all in the span of 17 calendar days. It started at 12:01am, adding to the night running experience I would need to complete the Bigfoot 200 in August. And it took place at altitude, between 9,000 and 13,000 feet, adding an extra element of difficulty.

Pre-race Fireball shots. “Last Call.”

I sauntered up to the start line with 60 other runners in Fairplay, Colorado, shortly before midnight, all of us in good spirits. A 50 mile race with midnight start at altitude tends not to draw nervous newbies. Nor did the voluntary, pre-race Fireball shots.

This was a training run, but one I hoped to finish in under 14 hours. I was physically trained to do so, I knew, but the altitude would be the wildcard. My limited experience running above 9,000 feet always involved a feeling that my heart was beating out of my chest.

Runners milling about the start line, with temps in the mid-50s. The weather forecast, even through the night, looks near perfect.

I arrived at Aid Station 2 seconds before the cutoff, surprising myself. Time over the last hour had gotten away from me. Still, breathing the thin air was becoming easier, and the sun would rise in the time it would take me to traverse the 4.8 miles and 1,000 feet of ascent and descent back to Aid Station 3, allowing for faster movement over the technical trails in the daylight.

My favorite part of any day— when sunrise is an idea, but not yet a real thing. Mile 19. 5:45am.

I approached the third aid station just behind Panos, a Greek runner who, I would learn, lived in Milwaukee. Peanut butter wrap in hand, we departed for Aid Station 4 together, 11 miles away. We had 3 hours and 10 minutes to get there.

It took me 5:15.

Quite simply, we made a wrong turn shortly after departing the aid station. We got off course in a way not easily untangled. We stopped multiple times to consult the map and course description on our phones. We got onto forest service roads marked with the pink ribbons signifying the race course, but that were numbered differently than anything in the course manual. We tried following shoe prints in the sand.

By the time we’d finally rejoined the correct course, with the help of Victor, the runner in last place, we’d run 10 miles, but were still an additional 8 miles from the aid station. We had 35 minutes to get there to make the cutoff.

I was hot. At 9:10am, the sun was beating down from a cloudless sky, and I was still dressed for an overnight, mountaintop low of 39 degrees; my “day clothes,” sun glasses and sunscreen were waiting in my drop bag at the next aid station, where I already should have been.

Undoubtedly dehydrated and sort of hungry, I’d been rationing my food and water for the better part of two hours. We couldn’t make it 8 trail miles in 35 minutes. My brain knew this, so my heart gave up.

Panos had a different strategy. If we come barreling strong into the aid station and tell them we got lost, he thought, they’ll let us continue on. After hours wandering the trails together, I watched him pull away from me. In little more than five minutes, he was out of sight.

I stopped at the top of a small hill around 9:15am, tying my pullover around my waist, stuffing my black, long sleeved shirt alongside my water bladder, and looping the UltraSpire, waist-mounted lamp belt I’d been wearing since midnight to the back of the pack. I’d always been reluctant to don only a sports bra under my vest, for fear of blisters. Now I thought, fuck it. I was hot.

And my heart wasn’t in it. I walked, sometimes quickly, and sometimes at an indifferent stroll, the remaining seven miles to the aid station. Not because I couldn’t run, but because, like the decision to play Keala Settle’s This Is Me from my phone in my pocket, it was just what I felt like doing in the moment.

Approximately a 5k left to walk before my “race” would be over.

I officially DNFd at Aid Station 4, Mile 32, having run approximately 42 miles. Panos’s race too, was finished at Aid Station 4, despite his push to carry on.

And, as I look for the lesson in the DNF, something I could have controlled, it is Panos that rises tall. As it turned out, we were two of a half-dozen or more runners who got lost leaving Aid Station 3 and missed the cutoff. Whether or not the course markings were bad, many a runner has gone astray even with clear course markings. Just ask Jim Walmsley. What I take away is a lesson from Panos’s heart, which never left that race. Despite the fact we’d been moving at precisely the same speed for the first 9 hours, he arrived at Aid Station 4 20 minutes ahead of me. If he’d been allowed to continue, it would have meant that our getting lost was only a barrier for one of us. A mental barrier, at that.

I take away from Panos that, no matter what happens, my heart needs to stay in the race.

Back at the finish line, with triumphant runners coming in, Panos and I shook hands and wished one another the best. We were sincere, in a way only ultra-runners understand. Still, I think we both knew he was the bigger man this particular day.

In three weeks I will run the White River 50 Miler, my last, real training effort before Bigfoot. I will lead with my heart.

I soothe my bruised ego with a Twitter nod to elite ultra-runner, Jim Walmsley. Even Cowboys make wrong turns.

Saturday, May 12, 2018 5:01pm Orcas Island, Washington

You’re okay. You’re okay. It’s okay. You’re okay. The phlegm formed a shallow pool in the back of my throat as I sniffed and wiped my eyes where tears started to form. It’s okay, I said out loud, for a fourth time, my voice breaking with fear. You’re okay. It’s okay.

The final, 1,000 foot climb to the top of Mount Constitution rose before me like a dinosaur’s broad back. I’d spent the last 30 minutes bounding, with as much speed as I could muster after 11 hours of running, down steep switchbacks, searching hopefully for the last, hard right turn at the place where the trail turned upward again. Only if I reached this place by 5:00pm would I have the chance to summit Mount Constitution, Mile 45 of 50, by the 5:45pm aid station cut off. In my head, I’d been alternating between Queen’s Keep Yourself Alive and Fall Out Boy’s Sugar We’re Going Down [Swinging].

Now, I was here.

Saturday, April 20, 2018 12:44pm Ellensburg, Washington

“Welcome to the Aid Station. We’ve got water, Coke, and a car to take you to the finish.” I was 14 minutes late.

I smiled broadly at this guy who I’d seen at races before but whose name I didn’t know. “Thank you,” I said. There were three other runners circling the aid station, their lilting voices indicating they too were not devastated to have been pulled from the course at Mile 15.5 of 31.

“It’s my first DNF,” I told one of them, shrugging. “I did a 100 miler two weeks ago. I guess my legs are still tired.”

After 14 ultra-marathons in two years, it was bound to happen sometime. DNFs for ultra-runners are like cuts and burns to a chef – you rather they wouldn’t happen, but they do. When, at 12:00pm, having completed 5,000 feet of climbing in just over ten miles, I’d looked down at the red dot of an aid station in the distance and realized I had only 30 minutes to get there, I’d stopped to take a selfie. If I was going to DNF, I may as well take a few photos first.

I’m happy that it’s this race I’ve DNF’d, I told myself as made the descent to the aid station where I’d be pulled off course. The Yakima Skyline 50k is difficult and, just two weeks earlier, I’d completed by second ever 100 mile race in brutal conditions, finishing triumphantly as the 8th woman over all. Yakima was a lark. And, besides, I was also registered for the 25k the following day. The sun is shining. I’m having fun. I’ve DNF’d and I don’t care.

At Mile 7 of the Yakima Skyline 50k.

Saturday, May 12, 2018 5:02pm Orcas Island, Washington

Forty-three minutes. It should be enough, I knew, to reach the top of Mount Constitution. It’s okay. You have enough time, I told myself. It’s okay.

I dropped my head, leaning forward onto the balls of my feet, and shifted weight onto my hiking poles. The inspirational lyrics in my head gave way to darker voices. You need to do whatever it takes. You cannot get pulled from this race. You. Can. NOT.

I’d told few people of the DNF at Yakima, and those I did tell I was quick to add the race had come on the heels of a 100 miler, justification for my inability to reach the half-way point in the allotted time. DNFs might happen to all ultra-runners, but they don’t happen to me. Yakima may have been arguably justifiable, but I couldn’t justify two DNFs in successive races. I needed to make it to the top of Mount Constitution by 5:45.

Saturday, May 19, 2018 6:36pm Seattle, Washington

I ran into the aid station to the sound of cheering volunteers. To my right, the Race Director stood with his watch, a handful of competitors surrounding him. Doubled over and breathing heavily, I looked at my own watch, trying to make sense of the numbers. “You have 24 minutes,” he said.

“Fuck,” I responded.

Saturday, May 12, 2018 7:39pm Orcas Island, Washington

A group of girls sitting on the lawn stopped their conversation to clap, and provide a polite “Woooo hoooo” as I came down the final embankment, running for the first time in nearly 6 miles. Candice, the Race Director, sat comfortably in a folding chair under the red canopy. “Congratulations,” she said, as a volunteer draped a wood carved Orcas Island 50 Mile medal around my neck.

“Thank you,” I responded, willing myself not to tear up. I sighed. “It was a hard day.”

All smiles at Mile 20. The hard part was to come.

I’d reached the top of Mount Constitution at 5:36pm, nine minutes before the cut off. During that final climb, I’d struggled to think of the last time I’d worked so hard during a race. I couldn’t recall hurting – and wanting – this badly before. To have made it meant, simply, that I would be permitted to finish. The advertised finish line cutoff was 7:00pm, though the race (quite generously, I’d come to realize), would allow an official finish to anyone reaching the peak of Mount Constitution by 5:45. Smiling weakly at Jeremy, the Aid Station captain at the Peak, I’d departed for the finish line around 5:40, walking slowly.

Two hours and three minutes later, I reached the finish line, 5.5 downhill miles away, the second-to-last finisher by three minutes.

Saturday, May 19, 2018 7:20pm Seattle, Washington

The volunteer struggled with the portable microphone. “Could I have your attention,” she bellowed at the 30 or so racers and family members seated at picnic tables on the shore of Lake Washington. Dinner was served, and most were socializing and eating hungrily. “We need to do these awards because some people need to leave.”

“In first place for the women, is Jenna Powers with 60.06 miles.”

Caroline, the woman finishing in second, and Jared, the winning man, clapped loudly beside me. I stepped forward, collecting my certificate, trophy, and hand-painted winners’ plate.

I’d only signed up for this 13-hour race on Monday, less than 48-hours after completing the Orcas Island 50 Mile. Just 15 minutes from my house, it seemed like a good way to get time on my feet as I continue to train for August’s Bigfoot 200. I thought I could comfortably finish 50 miles in the 13 hours with a mix of running and walking, and had even invited a few of my non-running girl friends to swing by and walk one of the 1.5 mile laps with me.

Despite my laissez faire attitude (and impromptu chit chat walk breaks with other runners), I overtook Caroline for the women’s lead around Mile 39. At 10 hours and 15 minutes, I reached 50 miles, the first woman, and second overall behind Jared. Concerned about overtraining and injury, I decided to walk the remaining 2 hours and 45 minutes. After all, I’d done the 50 miles I set out to do; hitting that milestone at the front of the pack was just icing.

But at 6:20pm, with just 40 minutes left to go in the race, I was still in the lead by what I estimated to be around a quarter mile. While I’d been content to lose my race lead when there were still hours left, it suddenly seemed like a silly sacrifice with just 40 minutes. I’d completed 37 laps and so had Caroline. As long as I stayed in front of her on the course, I would win. Not being able to see her behind me to know how strong she was running, I took off with all I had. I estimated needing just one good lap.

After more than two hours of walking, the achiness in my hips and feet had all but disappeared. I felt good. Still, I was grateful to again see the start/finish line, where competitors who’d decided to go out for no further laps had begun to congregate with the race director, next to the large leaderboard. They clapped and “woo hoooo’d” as I came in, doubled over with exhaustion. I’d covered that last 1.5 miles – miles 57 through 58.5 on the day – in just 16 minutes. “You have 24 minutes left,” the Race Director said.

“Fuck,” I responded, to peels of laughter from the spectators. They seemed to think Caroline was close behind. If I stopped now and she kept going, she would finish victorious with 39 laps to my 38. As long as I stayed ahead of her, I would win.

I took off running for one more lap. As it turns out, Caroline did not.

Atop the leaderboard.

In the space of 30 days, I’d both DNF’d and won a race outright. I’d cried mid-course. I’d walked in fun and I’d walked in exhaustion. The next 30 will bring the same extremes, I expect. And, God willing, the 30 days after that. And after that.

“Sorry I’m moving so slowly,” I told the valet, as I rolled myself out of the driver’s seat of my rented Nissan Rogue, stopped in front of the luxury Umstead Hotel in Cary, North Carolina, shortly before 8am on Sunday morning. “I just ran 100 miles.”

“Oh!” The young man smiled. “You ran the Rock & Roll!”

I scowled as I opened the back door to retrieve my drop bags, my mind flashing to the radio ads I’d heard for Rock & Roll Raleigh, happening the same day thirty minutes away. “Um, no. Rock & Roll is a half marathon. Thirteen point one miles. I ran a hundred. A hundred miles.”

The valet was non-responsive. In his defense, I sort of snapped at him in a way that suggested I might have ended the sentence with, “you stupid idiot.” In his defense, most people can’t fathom it.

I’d run the Umstead in 2016, my only other 100 miler. I was back again, not to prove anything, but simply as an opportunity to test my fitness as I ramp to my main 2018 running goal, the Bigfoot 200 in August. In so doing, I’d hoped to better my 2016 time of 25:46 and, just maybe, break the 24 hour mark, a milestone at the 100 mile distance.

On Thursday, luggage and yoga mat in tow, I touched down in North Carolina to 60 degree temperatures and sunny skies. A cruel teaser, I knew, as the forecast for Saturday’s race had hardened into the undeniable: rain all day. Followed by rain.

Runners ready themselves inside the cabin that served as Race Headquarters. The start line, just feet from the from door, would remain nearly empty until moments before the 6am start. This is the last time runners would be dry for hours.

(This forecast would also cause me to callously lose all sympathy for Boston Marathon runners who, just eight days later, would face the identical conditions. In a moment of selfish frustration, I may have posted on one friend’s Facebook page who was lamenting the weather: “If I can run in it for 24 hours, you can run in it for 3.” She “liked” my comment, but ultimately chose not to start.)

Umstead is a “loop course.” Twelve point five miles, run 8 times around. At the start/finish is Race Headquarters (above), with an accompanying outdoor aid station. A second aid station is located at the 7 mile mark on the course. While such repetitive running can be tedious, it is a logistically simple blessing for runners like myself, on our own without crew. Like most others, I set up an area for myself at the corner of one of the HQ tables, including a large duffel bag full of the clothes I would need for the duration, and a pilfered, plush bathrobe embroidered with “The Umstead Hotel” that I would use as a cover-up while changing clothes in this very public area later in the race. (I also remember wearing the bathrobe at 2:45am, over my dry clothes, standing in front of the fire while my volunteer pacer, Stacie, spooned potato soup into my mouth from a styrofoam cup. I had just 12.5 miles to go. I might be making up the bathrobe part; but I’m confident the rest of it happened).

Racers at the start. It’s definitely raining.

I’d packed every last running and hiking jacket I owned; every pair of gloves and mittens; and had multiple shirts, pants, shoes and socks. Still, with a forecast that called for unrelenting rain from 6am until 2am, and temperatures that would peak in the high 50s midday, before dropping steadily to settle in the 30s overnight, my goal became quite simple: finish without hypothermia. Before I even set foot on the course, time no longer mattered.

All smiles nearly Mile 7 of 100. This first lap would be the only one I tackled without mittens (though I am gripping hand warmers). In fact, by Mile 25 my hands would get so cold inside my mittens, I would lose the ability to use them for the remainder of the race.

I’d set out hoping I could make the first three laps, possibly four, without needing to enter Race HQ to change clothes. But by the time I’d finished my third lap, comfortably running at a 24-hour pace with a small buffer, the rain was coming down so hard I thought it better to get in front of any threat of hypothermia and change into a dry shirt and leggings, as well as a fully waterproof coat and pants.

Mud puddles around the Race HQ aid station as night falls.

I would run in these clothes for the next 12 hours, while day turned to dusk turned to night, and the field got smaller and smaller. The challenge of cold rain is staying warm. For most, bundling up too much means sweating; and sweat turns frigid in a heartbeat. And therein lies one small benefit of being an incessantly cold person — despite being covered head to toe in waterproof hiking gear that doesn’t breathe, I would never once break a sweat.

Aid Station 2, Mile 7, luminous in the night.

But my hands. Two pairs of gloves, three pairs of mittens (one waterproof), handwarmers, zip lock bags… and I couldn’t prevent my hands from freezing into claws, making them completely useless to me. One might think, “What do you need your hands for? You’re running with your feet.” Yes, but… It would take me 2 hours over three laps to make basic clothing changes. At 3:00am, the rain and snow finally stopping for the night and time to make one last warm clothing change before the finish, it would take three people 45 minutes to change my pants, socks, shoes and bra, to zip up my various jackets, and to put on my final pair of mittens as I was incapable of moving any of my 10 fingers on my own. It was in this 45 minutes that I would abandon any hope of a sub-24 hour finish.

Around 2am, the rain turned to snow, before finally stopping altogether around 3:00.

In fact, I would finish in 24:43:09, as part of an elite and hearty group. Despite a race known for being “beginner friendly,” only 43% of starters actually finished, the lowest finishing percentage in the race’s 24 year history. (Around Mile 70, I would step up to Aid Station 2 for some ginger snaps and, seeing bodies strewn about under the long, heated tent, think that this is what a refugee camp must look like). I was the 8th woman overall.

I have used words like, “awesome,” and “amazing” and “fantastic” to describe my race. Nonrunners have trouble grasping this, given the weather and the distance. Had I the option, I would have preferred 60 degrees and sunny. But then maybe I would not feel so entitled to the brags. There will be plenty of sunny races.

I celebrated my first Umstead finish in 2016 with a tattoo of the race logo on the inside of my right elbow. Before the race this year, I contemplated whether I would get a second, assuming completion. I don’t think I will. This one just means more now.

“Why do you run so far?”

Shrug. I struggle not to say something stupid, and trip over my words. “I don’t know. I just. I just. I’m sorry. I’m having a little bit of imposter syndrome right now.” I smile, in what I hope is a charming way, and not a lame fan girl way, which is how I feel.

They look at me, confused.

“I’m 40 years old and I work full time. I’m a mid-packer. You’re the real deal.”

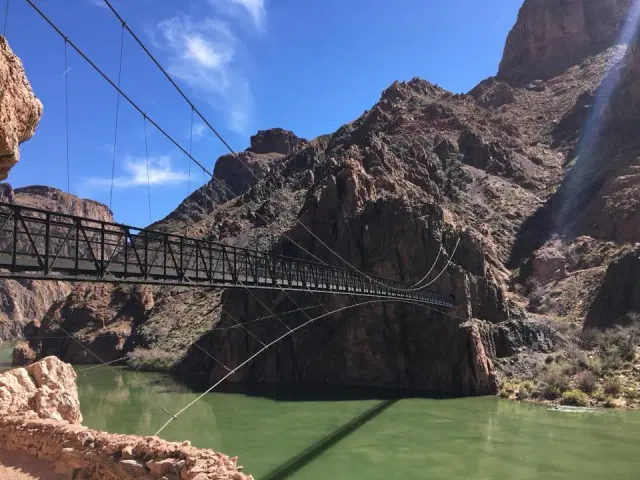

Day 1: I drop into the Canyon via the Bright Angel trail, which descends approximately 4460 feet over 10 miles to the Colorado River.

I’d first noticed the frayed back zipper pocked of my UD hydration pack the day before, when filling the bladder for what would be my first time running from the Grand Canyon South Rim (via the Bright Angel trail) to the Colorado River, and power hiking back up again via South Kaibab. This is not the traditional runner’s “Rim to Rim,” which starts at the North Rim and ends at the South Rim, as the former is closed for winter.

More than frayed, the back zipper pouch looked like it might bust open at some, inopportune time in the near future, and I made a mental note to pick up a new one at a local outdoor store, of which I assumed there were many in Flagstaff where I was staying, or in Sedona where I was going next. It wasn’t until the following day, having done the run in reverse down South Kaibab, and refilling my bladder just shy of the half-way point that I noticed offending brown spots inside the four-year-old bladder. Forget Sedona, I thought, this nasty thing wasn’t leaving Flagstaff.

I knew the ultra running elite men congregated in Flagstaff. Young, good looking, and winning everything lately, the “Coconino Cowboys” are the cool kids in the sport. And, while I had a vague notion that one or more of them worked at Run Flagstaff (the store I tried after REI, surprisingly, proved a useless stop), I never expected to actually see any of them.

The Colorado River.

Which is why I was more surprised than I probably should have been when I entered the empty store and one came around from behind the register to ask if I needed help.

Holy crap I know you. You just ran Black Canyon but dropped. I ran Black Canyon too. We were both there last year when you came in third; I got hypothermia. And I actually think I ran the TransRockies with you back in 2015. I only remember that because you guys all did the beer mile after day 3. I think you were naked. And there was a rumor that you were living out of your car and looking for sponsors. In any case, you have Lake Sonoma coming up next month, where you’ll try and place top 2 for a Western States golden ticket. I will follow the race on Twitter.

“Yeah; I need a new pack.”

I made one real rest stop over two days of running. Here, on the South Kaibab trail, which climbs nearly 5000 feet in 7.6 miles. Less than 1 mile from the trail head I sat, hot and tired, and stretched my legs. Within 5 minutes of stopping, I would be on the trail again for the final push to the South Rim.

Imposter syndrome is a funny thing. When he asked me what I was training for, the ultra-runner’s equivalent of “where do you work” or “what do you do,” I proudly told him, “Bigfoot,” as in the Bigfoot 200. He was impressed.

We talked about packs; what I would need to carry and for how long. And I did come clean that I knew who he was, and that I’d also run at Black Canyon, albeit “well behind” him. We talked about weather and terrain, and my upcoming 100 miler at Umstead in four weeks.

And that is when he asked me why I run so far, then mistook my idiotic stuttering as my having taken offense. He clarified, “I’m not asking because I’m judging.”

“Sorry. I’m having a little bit of imposter syndrome right now. I’m 40 years old and I work full time. I’m a mid-packer. You’re the real deal.”

“But I’ve only ever run a 100k.”

But you win.

I mumbled something about the fact that, with a 4:08 road marathon PR, I was never going to be at the front of the pack. That I’m built for distance, not for speed. And my answers were probably as unsatisfying for him as they were for me.

On day 2 I dropped in at South Kaibab, reversing the route I’d done the day before. Nearly 5000 feet down to the Colorado.

What I could have said, what I should have said, is that at some point while training for my first marathon in 2014, I secretly subscribed to Trail Runner, Marathon and Beyond and Ultrarunning magazines. That while I told myself the marathon was a bucket list item I’d wanted, at age 37, to check off my list, there was something stirring inside me. There was something about the glossy photos, not of road runners in big cities with huge medals, but of trail runners in the mountains and doubled over at the side of aid station tents. Where others saw suffering, I saw only magic. That within 23 months of completing my first marathon, I completed my first 100 miler, a race I’d signed up for without ever having run farther than 26.2 (though I eventually did complete a 52 miler during the training ramp, my first ultra). I should have told him that I get so excited on race morning I dance in my underwear. That sometimes I cry with joy on the trail. That ultra running calms me down and zens me out. That it’s the only time there are no emails. It’s made me a better employee and a better leader. It’s made me stronger in 100 ways. I should have told him that I found myself at age 38 on the far side of 26.2.

I wished him good luck at the Lake Sonoma 50 as I left the store. He wished me luck at Bigfoot saying, “I don’t know what it takes to run 200 miles.”

“Neither do I,” I joked.

Later that afternoon, he retweeted a photo I’d posted to the Coconino Cowboys about me wanting to know if I was one of them now that I’d run Grand Canyon twice. One of the others responded, “Back to back canyon days is crushing! Nice work!”

I waited a respectable 12 hours before liking the response.

The end of day 2. With rain the forecast beginning at 2pm, I’d taken off earlier than I had the day before, watching the weather move in from the North Rim. I would, in fact, make it back to my car parked at the Bright Angel trail head before the rain started, proving to myself that I have a good sense of my pacing; how long it will take me to get from point A to point B. Maybe I know a little about this ultra running thing after all.

It took twelve months to realize it was about more than the weather.

I was exhibiting signs of hypothermia and hypoxemia (low blood oxygen) when I crossed the 2017 Black Canyon 100k finish line. Just happy to be indoors at the Mayer High School auditorium race headquarters, I was shocked when EMTs announced to me, “you are in distress,” before attempting to strip me of my soaked clothing and get me to a cot, where I would remain for nearly two hours, a period of that on oxygen.

But all this time I thought the below 40-degree temperatures and incessant rain on the race course caused it. Only now, a year later and back at the Mayer High School track starting line do I realize that I began last year’s race that way: in distress.

Racers at the Mayer High School track starting line. It’s 40 degrees, but promises to warm quickly.

It would take me me six months to recover. It was not until I’d read an article by Elinor Fish on the impacts of stress on performance that I understood what I had been doing to myself with long, “always on” work weeks, followed by two weekend days with back-to-back long runs or, more often, race travel. According to Fish, if your “off day” from running is on a work day, it’s not really an off day.

An epiphany. According to Fish’s logic, I’d not had a day off in nearly two years.

Black Canyon was my 12th race of 2017 and, just 7 weeks into the calendar year, I had already run in Florida and in Dubai, as well as traveled to India on business; all many thousands of miles from my Seattle home. I would finally hit bottom in April, after 9 more races (including those in New Mexico and the UK), and business travel to Slovakia. Around the half way point of the Badwater Salton Sea 81-mile race in California, I left my running partner on the trail by himself, despite the requirement that we remain within 25 meters of one another for the entirety of the race. I was in in the midst of a massive panic attack and it was the only thing I could figure out to do at the time. I finished the race alone, losing nearly two hours by first waiting and then carrying on, then pleading with race officials not to disqualify me, while by partner slept in the back seat of the crew vehicle.

I came back to Black Canyon to prove something. Not that I could complete the course (I’d done that last year, despite the hypothermia); and not that I could finish under 17 hours, the time required to secure a lottery ticket for Western States (I’d done that too, despite the hypothermia). I came back to Black Canyon, not to kick the course’s ass, but to give it a bear hug. I wanted to prove to myself I’d thawed out; that I was no longer in distress. I wanted to love this race.

5:36pm, nearly 11 hours into the race

I took a lot of deep breaths. I gazed at the mountains. I stopped and turned around to face the sun. I looked down and, for the first time, noticed the rocks on the trail. Beautiful quartz, in white, purple, pink and coral. Like a child, I discovered that I wanted to pocket all the pieces I found irresistible.

When I started to feel light-headed, no doubt the effect of the warming temperatures and nearly 30 miles of running, I sat down at the Soap Creek aid station and drank 20 oz of Gatorade before continuing on. In more than a dozen ultras, it was my first time sitting at an aid station.

At Black Canyon City, the 60k finish line, my stomach turning on me, I accepted a volunteer’s gracious offer to prepare me some vegan broth; a powdery substance she scooped from a mason jar that I sipped like fine wine before popping two Tums and continuing on.

It was during that 8.8 mile stretch of trail between Black Canyon City and Cottonwood Gulch that I would unite with Benedict, a runner I’d met briefly earlier on in the race. Over the remaining 20 miles, we would accomplish that perfect partnership only trail runners know, of pushing and pulling one another along the trail, waiting and carrying on ahead without expectation and without apology.

Dusk makes its first appearance on the trail.

And at 59, a mere 5k from the finish, I enjoyed two cups of what I told the volunteer was “gourmet ginger ale.” An off-market brand I’d never heard of, that claimed to be made with real ginger but was still poured from two-liter bottles.

By the time I reached the finish line, it was nearly midnight. 16 hours and 34 minutes after I’d started. Dark. Cold to those waiting, though Benedict and I were in shorts. But I was still running. Nothing hurt badly enough to complain about. I was no longer in distress.

It’s January 14. I’ve been sitting on my final post of 2017 for two weeks. So long, in fact, that I’ve already completed my first race of 2018 — the Bandera 50k on January 6.

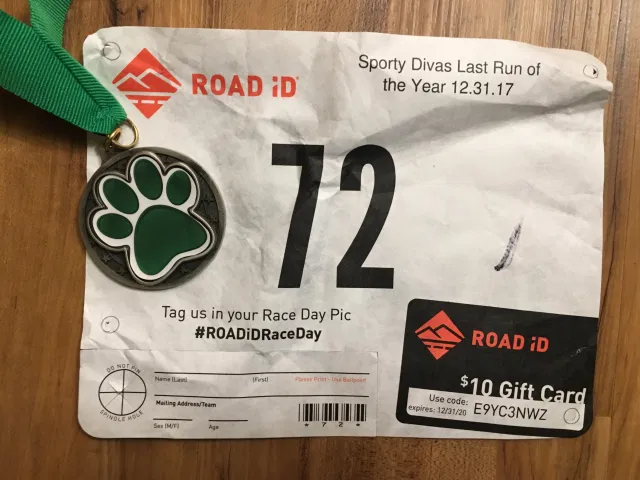

The 2017 race year ended with an anti-climax. I’d registered for the Sporty Diva Last Run of the Year, marathon distance on December 31. A 2.8 mile loop course, racers can complete distances of 2.8 miles, all the way up to 26.2. Because of where Christmas and New Years fell in 2016, this same race was actually number 1 in my quest to run 40 races in 2017 on January 1. While I didn’t love the course, I did come to love the people over the several races we’d run together during the year. I also really liked the idea of completing my quest with the same race I’d started it with.

But by lap 4 of 9, I was sick to my stomach. I walked much of that loop, before announcing to Rose, the Race Director, I was done. Just like that.

Bib #49: The Last Run of the Year.

In fact, I’d been sick a lot over the last few weeks, something I didn’t realize until I found myself at Mile 27 of the Bandera 50k one week later, doubled over in an abandoned barn on the side of the course. Not how I wanted to start the 2018 race season.

2017 was about completing a personal challenge and supporting others but, underlying those laudable goals, it was a year about quantity. Excess. 49 races. 2018 needed to be different.

The 2017 medal count. I tried three times to take this photograph, but had to keep rearranging the medals to fit into the frame. Still, once I’d finished and returned them all to their designated door nob in my closet, I found two more on a chair I’d forgotten to include, as well as one in a purse, one in a backpack, and my two ultra belt buckles. Those never made it into a photograph.

I am one of those people who considers herself spiritual and not religious. That’s a comfortable way of saying that I see God all the time when I’m running, but only go to church for weddings and funerals. Still, I was receptive last year when my dear friend Tammy at Freedom Runner Girl introduced me to the Word of the Year, a practice by which you receive a word from your higher power meant to guide your year, rather than making a resolution. You can check out a great article about the practice here. My 2017 word, beacon, guided me through the 40 bibs project.

My 2018 word is sow, as in the planting of seeds. It’s about doing little things that will grow into something bigger later on. That means shifting focus from miles and onto things like my persistently tight hips and weak glutes; on stretching over Syrah as a means of relaxation after a long day. By asking what I am sowing with the decisions I am making, I will be focused on the inputs to running strong miles. And I know from my work as a Director at Amazon.com that, to get the best outputs, you need to focus on the input.

My 2018 goal is to complete the Bigfoot 200. It’s terrifying. Much scarier than running 40 races. But I also believe that my fear is a sign that this is exactly the goal that I should have for this year. I look forward to the journey, and I look forward to sowing the seeds that will get me there.

The first race of 2018: Bandera 50k in Bandera, Texas on January 6.

As I write this, there are 10 days left in 2017. When the year is out, I will have exceeded my 40 race goal by 9 races, and supported 27 other runners in races in 14 states and three countries from 5k to 50k. But the goal wasn’t to support 27 runners, it was to support 40. Where to find 13 runners in 10 days?

I hardly remember running before Run the Year. It was around this time in 2014, on the couch of my temporary corporate housing apartment in Seattle, where my husband and I had moved just two months before from Boston, that I stumbled across a tweet announcing that I could “run the year” — 2015 miles in 2015. Having just completed my first three marathons that year and running a total of 1400 miles doing so, the thought of running 2015 was, quite frankly, ludicrous to me.

I signed up immediately.

A Run the Year girl squad preparing for the Hot Chocolate 15k in Seattle in March.

By the time I passed the 2015 mark in December, I’d collected not only miles, but friends and supporters. It sounds silly, but I didn’t expect the latter.

Andy L., Jason, Jennifer, Julie, Sal (my spirit animal), Gary, Andy C., Tony, Taira, Delia, Rob … only a few of the people I’ve come to know over the last three years. Some win races and qualify for Boston; some run ultras; some walk their way to 2000 solo or as a member of four-person team; and some are just dong the best they can do every day. It’s all okay; we all support one another.

Members of Run the Year in the Walt Disney World Half Marathon in Orlando in January.

Everyone should have the gift of these people.

I am honored to partner with Run the Edge / Run the Year to give away 13 scholarships for the 2018 Run the Year program, a number they are going to match, for a total of 26 scholarships. Information about the scholarships, the program and how to nominate someone (including yourself) is available here.

I have just one race left in 2017, the Sporty Diva Last Run of the Year Marathon on December 31. And on January 1, I will begin counting mile 1 toward 2018 in 2018. Join me!

Run the Year members in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania for the Runner’s World Festival races.