By 4:00am on Sunday, I was back to normal. Sure, it was an ungodly hour, but it was approaching the ungodly hour when I am at my best. That time when the black sky of night slips into the deep blue of morning, still nearly an hour to sunrise. My favorite time of day.

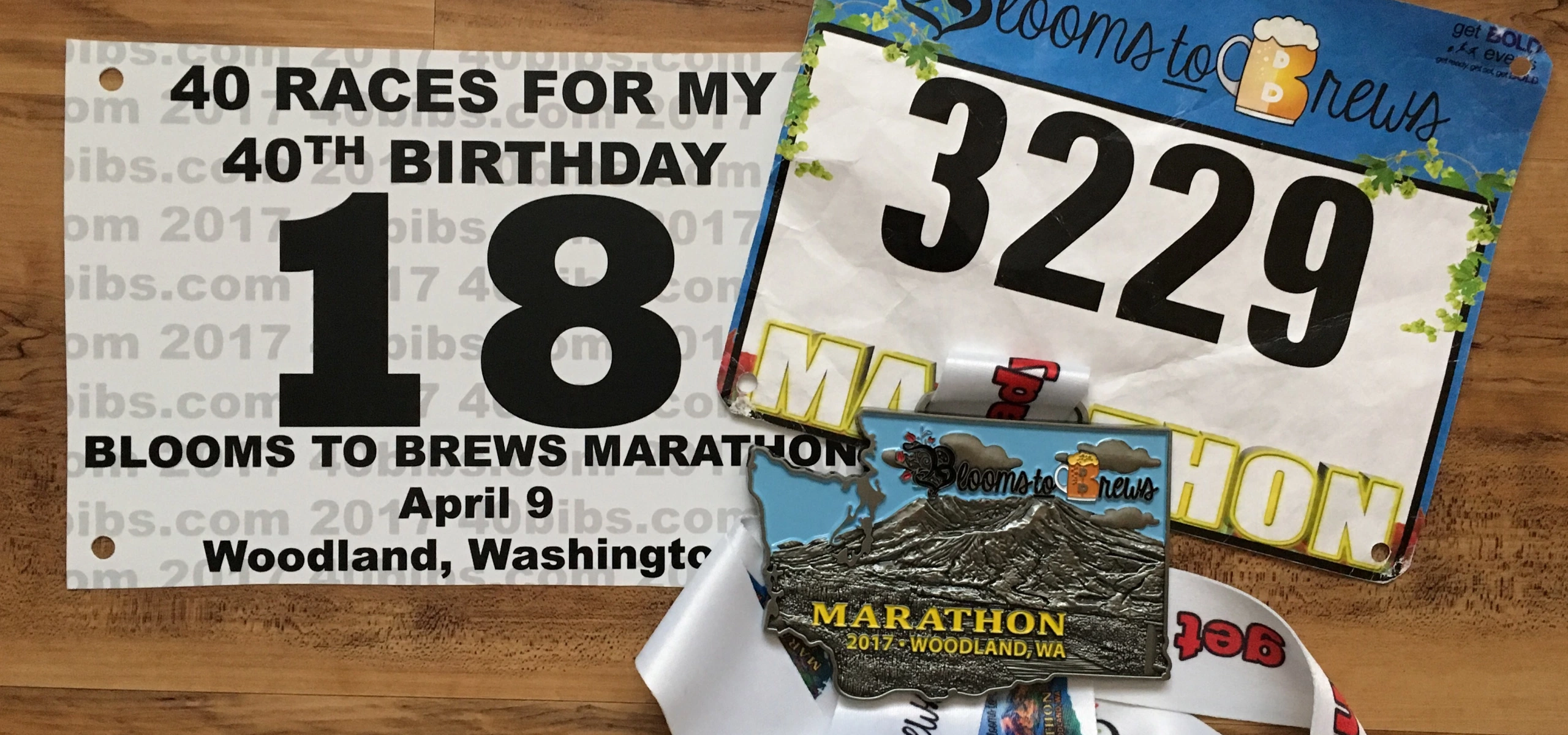

I made the two hour and twelve minute drive from Seattle to Woodland, Washington, 20 miles north of the Oregon border, engrossed in the heart of the Audible recording of Big Little Lies, all the rage right now in the 40-something female set. My failure at Saturday’s Squak Mountain 50k was not quite a distant memory, but it was distant enough.

The sun rises over Woodland’s farm land on the race course.

I hadn’t intended on making a race of it, but just 6 miles in I found myself struggling to stay behind the 4:15 pace group; I wanted badly to pass them. With a 4:13:41 marathon personal record from October 2016’s Chicago Marathon, I have no business running with the 4:15 group on a training run.

But at the split — 13.1 miles — I was still with them. Still not just holding on but holding back. And I started to think about how amazing it would be to PR the race, the day after a brutal trail half marathon and in the midst of a training week. At a 4:15 pace, I’d have to make my move with 9 or 10 miles to go to break 4:13; 10k to go at the latest. But at the 15 mile marker the pace group leader stopped for water, and I didn’t. The move was on.

My official finish was 4:14:01. 20 seconds short. “And to think,” I wrote on my personal Facebook page later that day. “Some people actually taper for these things.”

Race number 18, and marathon/ultra #6 for 2017.

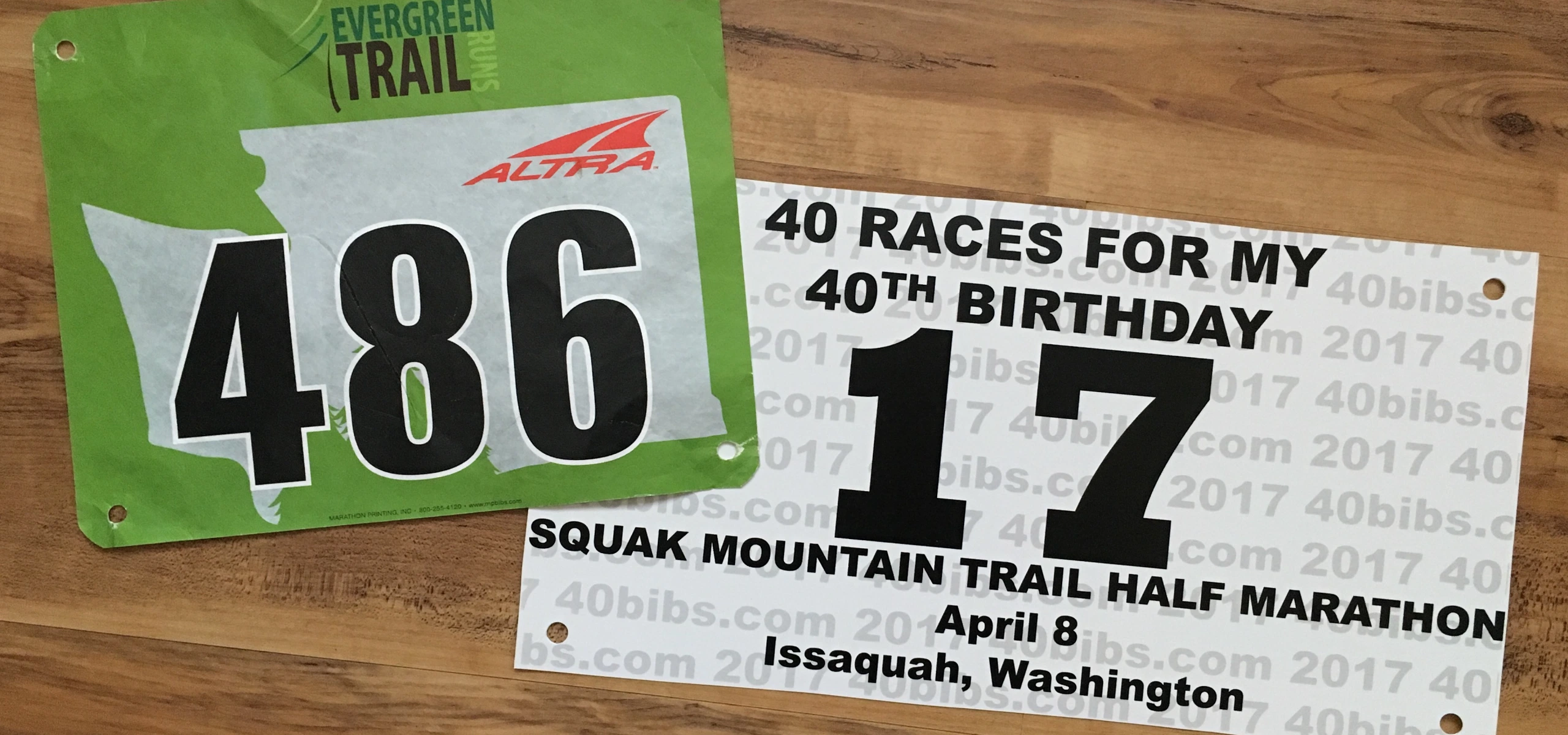

“486!” The volunteer shouted as I emerged from the trail into the parking lot that served as the Squak Mountain Trail Run main aid station. To her left, a large, black blow-up arch with the word FINISH plainly written in white lettering across the top.

“Can I take a half?” I asked.

“Sure,” she said, gesturing with her right hand toward the arch.

Like a soccer player who finds themselves suddenly, inexplicably and embarrassingly holding the ball, I was on the other side of the arch. The side that doesn’t say FINISH on it. Just like that, I cut my marathon in half.

I’d actually started my morning with a 50k. (You can check out my live start line video here, when I still thought I was going to run a 50k). Just three weeks out from the 81-mile Badwater Salton Sea, my longest race of 2017, I’m in the thick of long run training weeks. A 50k on Saturday, followed by the Blooms to Brews road marathon on Sunday, is not atypical. And, in Washington at this time of year, there are several road and trail racing options weekly, most allowing sign-up on the day of the race. So when I’d finally committed to both of these races less than seven days before, I glossed over a couple of crucial facts: Squak Mountain has over 9000 feet of gain in the 50k; and Blooms to Brews is 2.5 hours away, with a 7:30am gun time.

Full marathoners and 50kers, awaiting the start of the toughest course in the Evergreen Trail Run race series.

I write a lot about racing because it’s my passion, but I also have a high pressure job and a husband. There is laundry and groceries and meal planning, none of which happen unless I make them happen, and which only occur on the weekends because most workdays are 10 hours long. And we are dog-sitting for friends this week, at their house. I’ve added an hour to my weekday, traveling to their house after work to sleep, and then back to my own before my 4:15am run. All of this got more real as race day approached. As did the cold, driving rain the forecast for Saturday.

One of many long climbs in the 9800 feet of gain for the 50k. Marathoners would experience 8200; half marathon: 4100.

At 2 hours and 15 minutes in, at the 8-mile mark, I decided to drop to the marathon. I would have to traverse the same, half-marathon course a second time, plus a 6-mile loop section of the course a third time for a total of 31 miles, a heartbreaking thought. Not to mention the race’s 9-hour cut-off, which I was almost sure to miss. I have never missed a cut-off. It began to hail as we descended from the mountain.

A runnable section of the course, lush from the higher-than-normal amount of rain Seattle experienced through the winter.

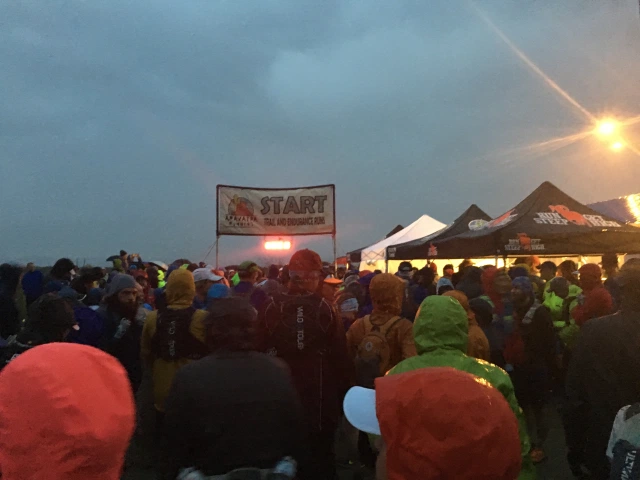

I could hear the clamor of the finish line at nearly 12 miles, the point where marathoners checked in, and literally turned around to go back out and do the course again. My watch read 3 hours, 37 minutes. Times two would be over seven hours. Rain would start within the hour. And I had drive home. And shower. And do a load of laundry. And then there are groceries. My alarm would go off at 4am for the 2.5 hour drive to another marathon in the morning.

Heavy wind and rain the night before crashed trees into the course in several places, forcing runners over and under.

I emerged into the clearing with little on my brain, except that I needed to be done. The race wasn’t too hard and I wasn’t hurting. But it was just the one thing on Saturday that I couldn’t do. And I needed not to do it.

“Can I take a half?”

For just a second, I stood on the other side of the finish arch in shock. Race rules allowed transfer from one race to another mid-event, so this was not a dreaded DNF (“Did Not Finish”). I would be listed as an official half marathon finisher. Still, I’d never done this before. I worried that I had somehow opened horribly magical door giving me permission to drop out of races in the future. I went home and did 7 more miles by my house as a sort of penance.

Quitting is not okay. But restoring balance is. I was way out of balance on Saturday; it took walking through that finish arch after 3 hours and 37 minutes to fix it.

(And if I did, in fact, open some magical door on Saturday, it didn’t lead to race failure. My alarm would go off at 4am on Sunday morning for the long drive to Woodland, Washington, where I would run the second fastest road marathon of my life, missing a marathon PR by just 20 seconds.)

We all remember our first. First 5k. First half. First marathon. First trail race.

First race in Europe.

With a job that can take me (voluntarily or otherwise) to more than 20 U.S. states and six continents, I have an easier time than most justifying a destination race. So when a colleague scheduled a business meeting in London, I was on the ahotu international marathon site before confirming with him that I would, in fact, attend his meeting. In a matter of minutes, I had registered for Manchester Canalathon 50k, a two-hour train ride from London. (And then I accepted the business meeting).

To be clear, this was not my first race outside the U.S. In fact, my very first marathon in 2014 was at the Great Wall of China and, earlier this year, en route to a business meeting in India, I’d stopped in Dubai to run the Standard Chartered Dubai Marathon, Race #7 on the year.

Posing with my first ever marathon medal at the Great Wall of China while friends and family in the United States slept.

But the Great Wall and Dubai races were international fields; races that, in many respects, are identical to Boston or New York or Chicago; featuring many thousands of runners from all over the world such that you get little sense you’re not at “home,” apart from the scenery (in China, anyway. The Dubai course looked like any hot, dry city with greater-than-an-average-number of mosques and few women.)

The Canalathon was different. It was a legit, non-Americanized race. Here’s how you can tell:

It was a 50k/75k/100k: Fair, these distances all exist in the U.S. But anyone who has run one will tell you that trail races, especially ultras, are decidedly more low-key than road races. A race like the Canalathon draws just a couple of hundred people at most (264, in fact, across all three distances), making it a “local” event, akin to your neighborhood 5k. (Okay, 5k times 10 or more). While I have no way to confirm, I’d bet my race medal on the fact I was the only American in a sea of Brits.

It’s not “race stuff,” it’s a kit: Sure, they speak English in Manchester. But not the English we speak in the U.S. So, the night before in my hotel I wasn’t busied by “laying out my race stuff” the way I typically am at home, but instead readying my “race kit.”

And it’s packed for the zombie apocalypse: Canalathon represented my 7th ultra since January 2016, and the first one I’ve ever participated in that didn’t allow drop bags — individualized bags runners leave at certain spots in the race (typically at aid stations) where they can stash extra clothing, a change of running shoes or other necessities. As ultras can last five hours on the short end, and over 24 hours on the long end, sometimes you need things as weather or other conditions change. But no drop bags were allowed at Canalathon. Instead, there were strict requirements about what needed be packed in the kit to be carried on our backs (or, a backpack in U.S. parlance). Specifically: (1) an extra shirt; (2) a waterproof raincoat with taped seams; (3) waterproof pants with taped seams; (4) a hat; (5) gloves; (6) a headlamp; (7) a whistle; and (8) two foodstuffs (like chocolate or a granola bar). No joke — race officials checked for all of these items before we were allowed to step onto the course, and warned that, if we failed to pass a random, spot inspection mid race (by ditching some of these unnecessarily bulky items, for example), we’d be disqualified.

Those that have run ultra before are reading this and thinking, this is ludicrous. And, if you’ve never experienced an ultra before, now is the time to think to yourself, this is ludicrous.

The Canalathon course traversed a wide, flat, dirt and stone trail from Manchester in the south to Sowerby Bridge, 50km to the northeast. At no point during the race are runners more than a 5 minute walk to civilization; 10 minutes to a pub, even. I point this out because I’ve never been required to carry this much gear in trail races at 14,000 feet in Colorado in the summer where you can experience freak rain or snow and can be up to several hours from aid if you need it. And, sure, I’m the person who was treated for hypothermia at my last ultra, but the weather for my last ultra also wasn’t this:

Fifty-five degrees, and not a cloud in the sky or in the forecast for days along the Canalathon trail. Good thing I’m carrying a raincoat, rain pants, a hat, gloves and headlamp for my 5.5 hour race that starts at 8:30am.

“Hey, you never know,” I heard the race official performing another runner’s bag check say. No; I’m pretty sure I know.

And NO HEADPHONES! Okay, a lot of races discourage headphones. But the last time I’d received an, ANYONE CAUGHT USING HEADPHONES WILL BE DISQUALIFIED warning was during a half-marathon in 2006 (where I found my rule-abiding self surrounded by runners in headphones, none of whom were disqualified). In 2006 Miley Cyrus debuted on the Disney Channel as Hannah Montana, and iPhones weren’t invented yet. You get my point; we’ve evolved.

And no electrolyte: Ultra-marathoners are alternately fuel obsessed and fuel agnostic. For example, the same runners who insist they can only race with a specific brand and flavor of electrolyte drink also have no qualms about eating cold bean burritos, moderately stale pizza, and scalding, sodium-laden Campbell’s tomato soup mid-race. Most ultra aid station offerings read like a megaband backstage buffet rider (minus the alcohol). After 50km or more of constant forward motion, the body wants what the body wants.

Canalathon’s two 50k aid stations (few and far between by the way), get two stars. There were these cut up peanut buttery fudgy things that, surprisingly, were not very sweet (much appreciated after standard gels and gummies start to feel as though they are burning away your stomach lining from the inside out); some bananas (not my fave); Coke (love); a little hummus; and no electrolyte. Again, for the uninitiated — imagine showing up to a wedding reception hours and hours from civilization for a couple that you don’t know and learning it’s a “dry” event. Had you known, you may have made a different choice.

But … lest you think I regret my European race adventure — think again! Races, for me, are like chocolate cake — even when it’s bad, it’s not that bad. Canalathon wasn’t even bad, only different than what I experience in the U.S. And isn’t that why we travel in the first place; to experience something that we can’t experience at home?

The Canalathon medal – much nicer than my other 50k medals (made of wood, glass, ceramic, and plastic). Maybe there is something to this European race thing.

I will remember my first European race fondly, and look forward to my next first race adventure!

It’s 83 degrees, and the marchers have been out there for nearly 12 hours.

I’m sitting on my hotel room bed, typing my blog and enjoying a movie and a glass of wine. Before that, I made an emergency trip to the mall across the street after my hair dryer broke mid-blow out. Before that, a shower. A post-race snack at a local pub. The 40-minute drive from the White Sands Missile Range. My own race finish. And, in all that time, the other racers have been out there on the course.

Opening ceremonies at White Sands Missile Range, near Alamogordo and Las Cruces, New Mexico, began at 6:35am. 7,000 marchers participate.

Sun rises over the Missile Base during opening ceremonies. While a chilly 59 at sunrise when this photo was taken, the temperature would climb to 91 degrees during the course of the march.

My friend, Robert, and I commented as much on the drive back to the hotel, when we could see marchers out our window around the 16 mile marker, the temperature nearing 90. This is, after all a “death march.” (Check out my live, start line video here).

Members of the Black Daggers parachute demonstration team show off their skills before the march.

Begun nearly 30 years ago to commemorate the Bataan Death March, the Bataan Memorial Death March drew 7,000 marchers in several categories for this, the 75th anniversary of Bataan. Most notably, the Military Division, requiring marchers to wear full, regulation uniforms for their branch and unit; and the Heavy Division, requiring marchers to carry a 35 pound backpack for the entirety of the 26.2 mile race.

Marchers in the Heavy Division weigh their packs the day before the race. Bags will be weighed by race officials when marchers cross the finish line. Anyone not meeting the 35 pound requirement will be disqualified — after their finish.

The original Death March was not so easy. On April 9, 1942, the Japanese Army forcibly transferred 60,000-80,000 Filipino and American prisoners of WWII, forcing them to march on foot approximately 60-70 miles.

The march was characterized by severe physical abuse and wanton killings, and was later judged by an Allied military commission to be a Japanese war crime. – Wikipedia

Thousands died along the way.

And thousands came out on the morning of March 19 to honor them.

Marchers coming out of the aid station around mile 8.5. After this short downhill portion, they will climb over 1000 feet over the next four miles.

A mix of paved road and sand trail (approximately 20 miles of the latter), the march is akin to a trail race.

Marchers coming out of the aid station at mile 14.

With high temperatures, deep sand in places, and the majority of participants in full military uniform and/or carrying 35 pounds, it is a slow race. The final finishers in several categories crossed the finish line over 14 hours after beginning, right around the time I was eating dinner and finishing my second glass of wine.

A lover of long distance races, I don’t typically have the “easy day.” But running in the Civilian Light Division, in technical shorts and a t-shirt, and with nothing but my body weight and a small, hand-held water bottle, I am acutely aware that my own 26.2 could not have gotten much easier. I’m reminded of the poem written to commemorate the original, 1942 march and read at the opening ceremony:

We’re the battling bastards of Bataan; No mama, no papa, no Uncle Sam. No aunts, no uncles, no cousins, no nieces; No pills, no planes, no artillery pieces. And nobody gives a damn. Nobody gives a damn. – Frank Hewlett (1942)

The marchers and I can’t go back and change what happened in 1942 but, in our own ways, we can all give a damn.

Reading up on the original Bataan March, from the comfort of my hotel room after my race. The final finishers will march on for 3 additional hours.

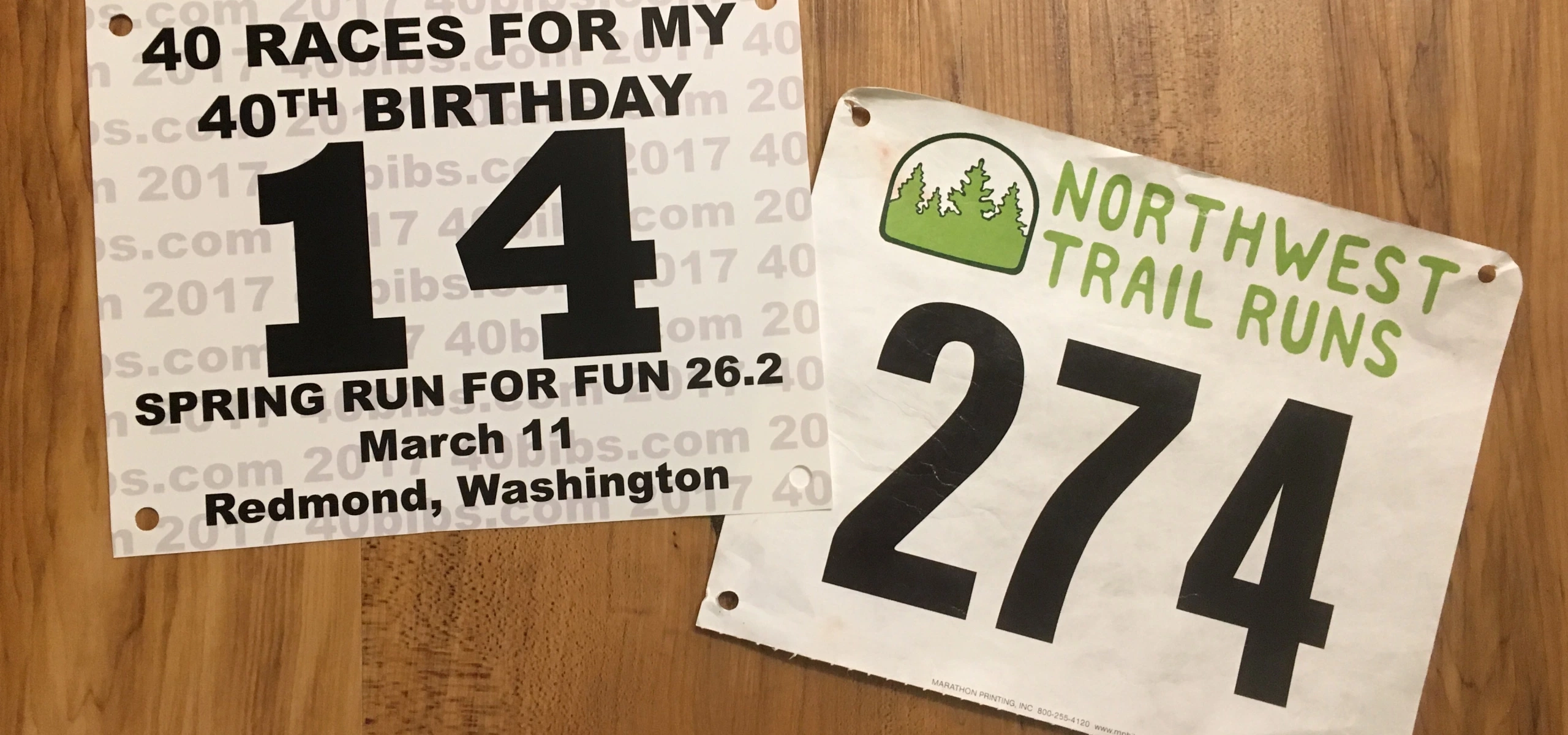

Perception: the way in which something is regarded, understood or interpreted.

Perception is a funny thing, especially when interwoven with memory: the faculty by which the mind stores and remembers information. For example, Saturday’s weather forecast for the Northwest Trail Runs Spring Run for Fun was clouds for the 8:30am marathon race start, with an 80-100% chance of rain from 9:30am until 2:00pm; the entirety of the race. I thought that, of my 14 races this year, 10 of them had to have been in the rain and/or otherwise terrible weather. I even commented as such in my live, start line video.

It was a dry start for the 60 marathon runners at Redmond Watershed, but the rain would begin one hour into the race, at the same time an additional 142 people began the 5 mile, 10 mile and half marathon races.

The beauty of a race blog is the objective evidence it leaves behind. It has actually only rained in three of my races, not 10. And this got me thinking about why my perception was so off. I came up with a few reasons:

Temporal proximity. This is the obvious one. It has rained for two of my last three races. We remember what happened most recently. And while I’ve raced in the rain three times in total, there were three other races I ran in which it rained during the day of the race, even though I didn’t actually run in it. I understand psychologists refer to this as reconstructive memory. I remember it raining during some races because I both raced and it rained in the same day, evening though they didn’t actually happen at the same time.

Expectations versus reality. Now it gets interesting. Runners plan. Training plans, meal plans, race week plans, night-before plans, race morning plans, pacing plans, fueling plans, drop bag plans… We like to control absolutely everything we can control to ensure that our races go precisely how we expect them to go. In all of that planning — often times months in the making– there is only one thing we cannot control: the weather.

Races 2-5 this year were at Walt Disney World in Orlando, where it is typically in the 60s overnight in January. This was the case for races 2 and 3, but severe rain and thunder hit on the morning of race 4 and, on the on the overnight before the 5:30am start of race 5, temperatures dropped into the low 40s. Living in Seattle, I run in the 40s all the time. But I hadn’t planned for it in Orlando. I purchased enough cold gear ahead of time to be comfortable during the race (including a hat, gloves and hand warmers), I recall that marathon as being freezing cold.

I’d started the week in shorts, but I ran the Disney World Marathon in Orlando with capris under by running skirt, two t-shirts and a long-sleeved pullover, ear warming headband, and hand warmers stuffed inside my gloves.

Similarly, the 2016 Black Canyon 100k outside of Phoenix was reportedly in the 90s. But race day 2017 was in the low 40s, with torrential rain for most of the race. I handle heat the same as or better than the average runner. Cold, on the other hand, especially wet cold, is disastrous for me. In was treated for hypothermia and hypoxemia when it was over, despite having all the proper gear; more clothes, in fact, than most of those running alongside me.

“Fun” at the Black Canyon 100k, just 19 miles into a 62-mile day.

When I registered for Disney and Black Canyon, I expected warm weather races. And even though I’d known the actual forecast before I stepped up to the start line and was dressed accordingly, in my head remained the expectation of warm weather. More so than remembering the actual weather, I think I remember that the weather didn’t match my expectations.

Seminal experiences. It’s been less than 30 days since I ran the Black Canyon 100k. It was traumatic, physically, mentally and emotionally. I can’t say definitively that my race would have been better if not for the driving rain, but I know it would have been different. I learned a lot about myself during that race, much of which I’m still processing. That race has changed me; I’m still figuring out how profoundly. Regardless, I feel confident I will not forget the rain on that day.

The marathon course in Redmond got progressively muddier as the day (and the rain) wore on. After the race and back at home, I would take off my race tights and socks in the shower, only to discover my bare feet were actually caked with mud as well.

I finished well in Redmond, given that this was a training run for an upcoming ultra at the end of April, and given the conditions. The photos will keep me honest — it did, in fact, rain during the race, unlike the dry-sky and sunny photos I have from 11 other races before it.

My next race is just one week away, the Bataan Memorial Death March marathon in New Mexico. The forecast is calling for overnight lows in the 50s, with a daytime high of 81. My body is not accustomed to such conditions. Despite 2017 races in Orlando (#2-5), Dubai (#7), and Phoenix (#13), I’ve not yet run in anything over 70 degrees. At this point, I welcome the opportunity for shorts and a tank top. I secretly hope it will usher in a series of warmer-than-expected races. Perhaps by June, I will be posting about all the races being too hot.

Google defines fomo as, anxiety that an exciting or interesting event may currently be happening elsewhere, often aroused by posts seen on a social media website. I having raging race fomo.

So when Jennifer, a member of my online running group Run the Year, knowing I lived in Seattle asked if I was running the Hot Chocolate 15k, I registered before responding to her.

Members of the Run the Year online running group from as far away as Phoenix, sharing some team spirit before the 15k.

For the uninitiated, the Hot Chocolate series is a thing. Held in 25 cities in the U.S. and Canada, the race is known for the swag and the sweets: there are a lot of both. As a result, it draws a lot of runners — more than 10,000 in Seattle between the 5k and 15k, with proceeds going to support the Ronald McDonald House Charities. (Check out my live start line video).

4500 runners, ready at the 15k start corrals. Another 6,000 ran the 5k.

The Space Needle marked both the starting and the ending beacon for 15k and 5k racers.

For what is the epitome of a “fun run,” I was a little surprised by the course, which seemed to hit all the hilliest parts of Seattle inside of 9 miles. While I opted not to partake in the strawberry and chocolate marshmallow stops to get me through, I did happily stop for a mouth full of M&Ms around mile 6.5. Because, as I understand it, that’s what you’re supposed to do at Hot Chocolate races.

With a mile left in my race, those in the latter corrals are working hard, with more than 5 miles (and 4 significant climbs) between them and their hot chocolate.

While the sun was out for my race, it was still only in the mid-40s, making it a perfect day for hot chocolate when the race was over.

The coveted Hot Chocolate finisher’s mug. Sure, you can see the healthy banana, but there’s fudgy dipping sauce in there that you can’t see.

I think my first Hot Chocolate was a success! I got to meet some amazing women from my online running group; I completed race #13 for the year; and I got to each chocolate disguised as “race fuel.” It doesn’t get much better than that!

The one thing at the Hot Chocolate race that I couldn’t eat. But I tried.

Some people think we’re crazy for running long distances. Often times, we are not doing it for ourselves, but instead to support good causes. And sometimes we do other crazy things to support good causes.

In February, Julie ran a 5k to support the Special Olympics of Colorado. And then she took a Polar Plunge, jumping into a freezing pool at the Denver Zoo!

Congratulations on your splash and your dash, Julie!

I am really enjoying my running journey to 40 races this year, but I’m also loving hearing the stories of so many men and women with amazing running stories of their own. One of those people is Libi, who ran the Snowball 5k in Virginia last weekend.

Libi is one tough lady! After losing some serious weight in 2016, she had the courage to sign up for her first half marathon, coming up in March. She intended to use the Snowball 5k as a training run, but just a couple of weeks before the race, Libi got pushed off the pavement and injured during a charity 2-miler. She continued to push through for a trail race the very next weekend, and wound up in the orthopedist’s office. By three days before the Snowball, she was in some serious pain, and contemplating dropping out of the race.

On race morning, the unseasonably warm 65-degree temperatures in Virginia beckoned her, and wearing two knee braces, Libi set off for the race, telling herself she’d even walk it if she needed to.

Libi, showing off her hard-earned third place medal.

Libi not only ran the entire 5k, but she did an extra .5 mile (as a volunteer sent her in the wrong direction), and still placed third in her age group! Even more fantastic, all the pain in her knee is gone! And this is especially good news, because Libi is now less than one month away from the Anthem Shamrock Half Marathon.

Congratulations on a great race, Libi, and good luck with your final weeks of half marathon training. You’re going to be great!

Sprinters are drama queens. Have you ever seen a sprinter come in second and not throw themselves to the track in a fit of ridiculous, self-important sobs? Marathoners are more resilient. When Team USA’s Meb Keflezighi slipped and fell just inches from the finish line of the 2016 Rio Olympics, he did push-ups before getting back up. Marathoners are my people. Ultra-runners are also my people, with their combination of intense self-determination and a touch of laissez faire, so often mistaken for just plain crazy.

“Have you been hypothermic before?” The EMT asked me from his seat on the cafeteria bench next to the cot where I lay prone, covered in a wool blanket, two sleeping bags and a mylar runner’s blanket. “Not that I’m aware of,” I answer, honestly. This is not the first race I’ve finished with blue lips; it’s just the first one where I’ve been cornered by the EMTs, made to strip and lie down, attached to an oxygen tank and told if my blood ox levels don’t improve they’d have to send me by ambulance to the hospital.

An hour later, long after my lips had turned back to their naturally rosey hue (my body having responded well to the threat of hospitalization), I can hear Jeremy, a runner wrapped like a burrito on the cot by my toes, telling Lloyd the EMT that he’s fine to go home. The blurry spots in his vision are still there, but he thinks they’ll improve once he gets outside [into the pitch black of midnight with the sideways rain]. And Shelly, on the cot behind me who has her legs elevated after fainting in the bathroom, telling another EMT that, while she’s still a little nauseous, she’s sure it will subside over the 40 mile drive back to her AirBNB. We’d all completed the Black Canyon 100k, and in times fast enough to qualify us for the 2018 Western States Endurance Run lottery, my personal goal and reason for running the race. (Check out my live, start-line video from Mayer High School).

Runners make final preparations while dry inside the Mayer High School cafeteria. Upon their departure, much of this location would be transformed into makeshift clinic for the bloodied (in addition to the typical skinned knees and shins, there were at least two bandaged face wounds that I saw) and the hypothermic.

It was a precarious race, even before it started. On Wednesday, Race Directors made the difficult decision to alter the original course, a point-to-point with four river crossings, to an out and back with no river crossings, due to potential flash-flooding in the area. This alteration would keep runners safe from the potentially raging Agua Fria River, but it would do nothing to shield us from the other effects of an Arizona desert downpour. 53 registered runners did not even start the race.

Runners on the Mayer High School track starting line, already soaked in the walk from the cafeteria.

“Shoe-sucking mud” is neither a euphemism nor an exaggeration. I’ve run in it most recently at the 2016 Rut 50k in Montana, where race-day snow and sleet-storms forced organizers to cut nearly 6 miles off the alpine course, leaving 26.3 miles of muddy sludge resembling brownie batter.

But this was different. The mix of mud and clay not only had runners, early in the race, expending significant energy with every, sliding step, but the clay stuck to our shoes. For every 50 meters we managed to move forward, we were rewarded with a ring of clay around our soles like thick, heavy flippers, forcing us to beat our shoes against surrounding rocks to loose it.

There is mud, and then there is this, less than 30 minutes into what is, for most, at least a 12-hour running day. (Courtesy of SweetMImages on Twitter)

By the time I reached the Antelope Mesa aid station — the first of 9 aid stations and just 7.3 miles into the race, I was already 10 minutes behind pace for the Western States Lottery cutoff. While I kept going, 19 others would drop at Antelope Mesa, 54 miles short of the finish line.

The day improved, as runners discovered the course beyond Antelope Mesa infinitely more runnable. By 11:30am, four and a half hours into the race, the rain stopped completely. Lowering my rain hood, I heard the quiet of the desert for the first time (rather than the monotonous swoosh swoosh of nylon against my ears), and took in the view from my previously-blocked peripheral vision. For the first time all morning, I thought the course might really be a nice one.

Six hours of dry skies reveals the beauty of Arizona’s Black Canyon. (Courtesy of Aravaipa Running on Twitter)

The seven mile stretch between the Gloriana Mine aid station (number 4), and the Soap Creek Provisional aid station at the half-way point turn around was a long one. I’d made up the original time lost at the beginning of the race, but as my watch ticked nearer to my goal turn-around time, I began to once again become apprehensive about the prospect of finishing within the Western States lottery cutoff. Every corner and hilltop held the promise of the turn-around point. But my goal time passed, and I could still see neon runner raincoats far into the distance. By the time I checked in at Soap Creek, I was an hour behind schedule.

And I was hurting. I’d expended so much energy in the early miles, first in trying to gain purchase in the slick conditions, and then in inadvertently running hard to make up time. I was apparently not alone. By the time I checked in at Soap Creek, with 13 hours left until the race’s official end, 44 runners had dropped out.

Runners are welcomed to the Bumble Bee aid station, which served both miles 19.1 and 42.2. (Courtesy of @jonchristley on Instagram)

The rain began again in earnest as I approached the Bumble Bee Back aid station at mile 42.2, with 19.1 miles to the finish. While still comfortable in my Geoduck Gallop Half Marathon long sleeved tech t-shirt and rain waterproof pullover, I used the opportunity to put on another layer — my North Face winter running jacket, underneath the pullover. Night would fall in the 6.7 miles to the next aid station, and I wanted to be prepared. In my preoccupation with remaining warm, however, I neglected the one item that was written on three copies of my race plan, highlighted in yellow — to take my headlamp with me before departing the aid station.

I was less than ten minutes beyond Bumble Bee when I realized my mistake, my audible “oh shit,” catching the attention of the man behind me, who I’d heard the aid station volunteer call “Stu” before we left. “What’s wrong?” He asked. “I forgot my headlamp at the aid station,” I said. In fact, my brother Stephen, acting as my crew for the race, had it in a bag he was carrying with him, and had departed for the car in the downpour immediately upon my walking away from the tent. While I was not too far away to go back to the aid station, my headlamp, I knew, was already gone.

I have never made such a potentially disastrous mid-race mistake in my life, and the following 6.7 miles played out as a mini-drama unto itself. Stu had an extra headlamp on him, his back-up, which he generously gave to me. He vowed he didn’t need it, but admitted that he wasn’t certain the lamp was waterproof; he thought it could possibly short out in the rain, and advised I try and wear it under my baseball-style running cap, as opposed to on the outside as most people do. While grateful for Stu’s generosity, I was still terrified of being caught in the dark without a light. I planned to just stick right behind him and draft off his waterproof headlamp when the time came. That is, until Stu announced he needed to make a bathroom stop. I had a choice: stand around and wait for a strange guy to pee against a cactus within eye-shot and potentially get cold in the process; or keep moving forward, relying on the non-waterproof headlamp. If I kept going, I knew I was likely to pull far enough away from Stu that he couldn’t catch me; but I was also far enough behind the next runner that I wouldn’t be able to catch and draft off him, unless I ran faster, expending energy I didn’t feel like I had, and convinced I would misstep and face plant in the process (a very real fear for ultra-runners on tired legs). In the end, my fear of getting cold outweighed my fear of being alone in the dark. Stu stopped, and I kept going.

Whether or not it was waterproof, the headlamp got me safely to the Hidden Treasure Mine aid station, where my brother was waiting. Still a little freaked out, I took not only my headlamp, but also my waist-mounted lamp which I’d brought as back-up. I would wear both for the remainder of the race, which I still thought I could complete within the Western States cutoff.

But this would be the last I would see of my brother. With nightfall upon the race and the rain still pouring down, Race Directors advised crew to abandon the aid stations entirely and go directly to the Mayer High School cafeteria and finish line. “The driving is really bad out there,” my brother told me. “I might not be at the last aid station.”

I could say the next 12.5 miles were a blur, but that’s not entirely true. I distinctly remember marching. Stomping, in fact, through ice-cold puddles as much as ankle deep, seeing nothing but the slop just feet in front of me. A couple of times the puddles reached across an entire jeep trail, and I heard someone off to my left utter, it’s a lake. (Video of this solemn march in the blackness was taken by runner @cierrecart on Instagram).

During this time, there was a fair bit of self talk, which for me comes in the form complementary, drill sergeant-like commands. You are strong, and this will only make you stronger! Not everyone can do this; but you can do this! You will not be weak! You are not in pain, you are resilient! And the chanting of names from my online running group, in a kind of Arya Stark reverse hit list. Channel Reggie, because she does funny race dances. And Julie, who is “growing and becoming.” Remember when Andy finally broke his 5k goal? Delia walks 3-5 mile blocks at a time and hashtags it #chunkingwithdelia. You are totally chunking with Delia right now. Ronald, Patrick and Gary are fast; be fast like them. And Sal is my spirit animal because he ran 100 miles in one day all by himself. The other Andy is going to kill the Buffalo Marathon…

And delusion. I walked into the Antelope Mesa aid station, looked around, and found I was too cold to actually do anything there. I still had half a bottle of Gatorade and three small bars in my pack, enough fuel (though maybe not enough fluid) to last the final 7.3 back to the high school. Despite the fact it had taken 1 hour and 40 minutes to slog this stretch at race start, I decided it would take precisely 90 minutes on the way back, as the ensuing rainfall had diluted the clay significantly, and I no longer cared about trying to step in a “good” place.

In truth, I needed the trek to last no more than 90 minutes, at least mentally. I was so wet and so cold, I could think of nothing but the high school. I was also hungry and thirsty, but the thought of biting into another packaged bar made my stomach lurch, and pulling my water bottle out of my front pocket (where it rested for easy access) felt like a bridge too far. I routinely completed 90 minute training runs without food and water, surely I could walk 90 minutes without it, I thought.

After 60 minutes, I could see the High School lights in the distance, and I decided again that I would be there in another 30. When that time came, I found myself, along with 6 other runners shadowed by their headlamps, continuing through town on what would be an additional 30-minute journey. It took me 2 hours and 1 minute to travel that last 7.3 miles. I crossed the finish line at 11:01pm with a time of 16:01:12, and good enough for the Western States Lottery.

By 11:05, paramedics where stripping me of my clothes, fumbling with vest straps, lamp hooks and watch band as I tried to describe how they worked, but otherwise looked on, a little dumbfounded. “I’m sorry I’m not more help,” I said, repeatedly.

I was treated for symptoms of hypothermia and hypoxemia, making for a great story, but sounding far more dramatic than I feel like my race warranted. That’s another characteristic of ultra-runners: we have incredibly short memories. From her cot (between trips to the bathroom to throw up), Shelly talked about the 500-mile race across France she’s doing this summer. I told her about the 81-miler I’m doing in April. And while I’m wondering if I should lay off the cold-weather races for a little while, the truth is that I’ve been a victim of bad weather, more than bad race picking. The Black Canyon 100k was 90 degrees in 2016. Maybe I’ll come back next year and run it under normal conditions.

The last time I ran in Seward Park, I was crying. I was 17 miles into the 2014 Seattle Marathon and, despite double-layered gloves and mittens, I’d lost the use of my fingers to Raynaud’s Syndrome, a disease causing the blood vessels inside the fingers to close in cold temperatures and stress, rendering my hands virtually useless. While you don’t technically need your hands to run a marathon, it’s awfully hard to take in fuel or water without them, hence the frigid, painful crying at mile 17.

Today was different, and not just because I’d since discovered the joy of hand warmers stuffed inside my gloves. My Better Half Marathon is a 5k, 10k and half marathon event drawing teams of two in the Lovers, Besties and Bromance divisions, as well as solo runners in the Lonely Hearts Club division. More significantly for me, it was my second half marathon in as many days. (Check out my live, start-line video!)

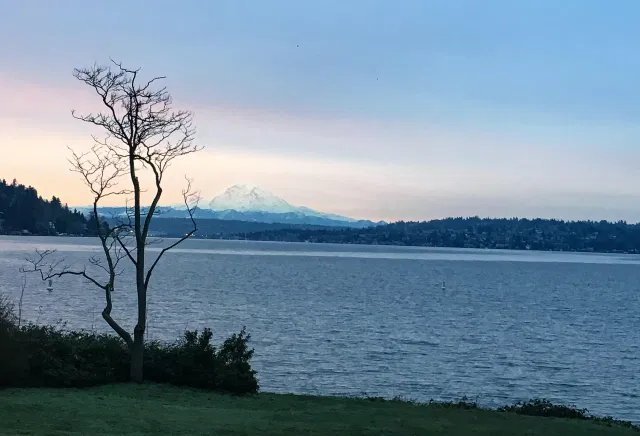

Mt. Rainier, rising more than 14,000 feet in the distance signaled a clear day for runners in Seward Park.

5k, 10k and half marathon racers ready to go in a sea of red, in honor of Valentine’s Day later this week.

I have run longer on consecutive days before. There were the back-to-back marathons I’d completed in Utah and Wyoming in 2015 to earn admission to the Marathon Maniacs, the 6-day, 120 mile stage race across the Colorado Rockies, the half and full I’d completed during Disney’s Dopey Challenge earlier this year, as well as numerous training runs totaling well above 26.2 miles over two days. It was not two half marathons that felt remarkable to me; it was the fact that they didn’t feel remarkable.

I don’t know when, precisely, this happened. I remember the first time I ran on two consecutive days. It was August of 2011. After a handful of half marathons over several years, which I’d trained for by running 3 miles on Wednesdays and a “long run” on Saturday progressing up to 12 miles, I’d decided I wanted to get faster. I signed up for the Runner’s World Half Marathon in October and bought my first training plan, which called for 4 days a week of running over twelve weeks. An unfathomable four days of running. I ran 3 miles and 4 miles on the first Tuesday and Wednesday; a total of 12 miles by the end of the first week. The persistent leg and glute pain didn’t subside until I got to week 4. But on race day, I shaved more than 5 minutes of my personal record. I’ve not run less than 4 days per week since.

Me and Runner’s World Editor (and 1968 Boston Marathon winner), Amby Burfoot, after my first Runner’s World Half Marathon personal record in 2011. I’ve run the race every year since, and the course is the site of my current half marathon PR, set in 2014.

Much has changed in the years since that first back-to-back run. I became a wife and a marathoner. I moved from the east coast to the west coast. And then I became an ultra-marathoner. With race tattoos (plural).

In 2015 I added a fifth day of running to my training plan and, in 2016, a sixth day. This weekend’s back-to-back half marathons were the races punctuating my taper for next weekend’s 100k, where I hope to qualify for the 2018 Western States Endurance Run lottery.

But I still cry at races sometimes when I’m really cold and can’t feel my fingers. More often, though, I cry because I am so happy, and I’m reminded how remarkable runners are. And how proud I am to be one.

One more medal for the collection.